The biggest Angular Universal gotchas, and how to avoid them

Angular Universal is a technology which allows you to create Angular apps that render both in the browser and on a Node.js server. This is useful for many reasons, the most important of which is generally considered to be SEO - universal rendering allows your application to be indexable by search engines such as Google.

While for the most part your Angular application should run on the server exactly as it does in the browser, there are a few gotchas, and a few adaptions you must make to your codebase for it to run smoothly as an Angular Universal app.

In this article I will address these gotchas, and discuss how you can work around them.

If after reading this article you would like to learn more about Angular Universal, the following Udemy course has a dedicated section on it, as well as covering many other important Angular concepts (affiliate link):

Angular - The Complete Guide (2020 Edition)

1) Avoid referencing window, document and other DOM specific globals

These globals include window, document, localStorage, indexedDB, setTimeout and setInterval.

Node.js does not have a DOM api and is also missing some of the other apis which are available as global variables in the browser, so any reference to these globals will throw an error - ‘window is not defined’, ‘document is not defined’ etc… In the case of setTimout and setInterval, you will not get an error as these globals exist in Node, but do have a slightly different api.

Specifically for server side rendering, we just need to avoid referencing these globals in code which runs during the first render of a page. eg. accessing window would not cause a problem inside of a click handler as this code would only ever run in the browser.

One approach to solve this problem is to use the isPlatformBrowser and isPlatformServer functions, which Angular provides in order to allow you to run code only in the specified environment.

import { DOCUMENT } from '@angular/common';

import { Component, PLATFORM_ID, Inject } from '@angular/core';

import { isPlatformBrowser, isPlatformServer } from '@angular/common';

@Component({

...

})

export class MyComponent {

constructor(

@Inject(DOCUMENT) private document: Document,

@Inject(PLATFORM_ID) private platformId: any,

windowRefService: WindowRefService,

) {}

ngOnInit() {

this.scrollToTop();

}

scrollToTop() {

if (isPlatformBrowser(this.platformId)) {

this.windowRefService.nativeWindow.scrollTo(0);

}

}

}

Note that in the above, we are not actually working directly with the global values document and window. Instead, we inject them via Angular’s dependency injection - this keeps our code decoupled and testable, and gives us the option to later inject different values for these Injectables based on the environment.

document is injectable via the DOCUMENT Injection Token which is part of Angular. In Node, this will inject a domino implementation of document.

To inject window in this way we must implement something ourselves by creating a WindowRefService:

/*

* This code snippet is based on

* https://juristr.com/blog/2016/09/ng2-get-window-ref/

*/

import { Injectable } from '@angular/core';

function getWindow (): any {

return window;

}

@Injectable({

providedIn: 'root',

})

export class WindowRefService {

get nativeWindow (): Window {

return getWindow();

}

}

This strategy will work for code which we write ourselves, but what if we are using a third party library which accesses window, document or other DOM globals?

JavaScript within a third party library may throw errors due to attempting to access these globals during our server render, but we have no control over the library’s code. In this case we can install a library such as domino, and then create a shim for the window and document objects in the server.

npm install domino

In our server.ts file.

const domino = require('domino');

const fs = require('fs');

const path = require('path');

// Use the browser index.html as template for the mock window

const template = fs.readFileSync(path.join(__dirname, '.', 'dist', 'index.html')).toString();

// Shim for the global window and document objects.

const window = domino.createWindow(template);

global['window'] = window;

global['document'] = window.document;

These shims will allow our 3rd party library to access the window or document globals without causing any errors.

A full example of a server.ts file which uses this approach can be found here.

2) Avoid manipulating the DOM via nativeElement (Angular < 6.1.0 only).

We often need to manipulate the DOM directly in some way, and in Angular we are able to manipulate a native DOM element using the nativeElement property of an ElementRef.

nativeElement exposes a HTML element from the DOM via the HTMLElement interface. But as this is part of the native DOM api, it does not exist in Node.

In Angular >= 6.1.0, Angular Universal uses domino as an implementation of the DOM in Node, and the nativeElement property of ElementRef exposes the domino implementation of HTMLElement. This means that we can now manipulate the DOM directly - in the browser nativeElement will give us a reference to the native browser DOM implementation of HTMLElement, while in Node it will give us a reference to a domino implementation of HTMLElement.

However, prior to Angular 6.1.0, code such as the following won’t work in a Universal app, as nativeElement will be undefined on a Node server.

ngOnInit() {

this.elementRef.nativeElement.classList.add("my-class");

}

We could wrap this in an isPlatformBrowser conditional, but things start to get messy if we have too many of these conditionals we have in our codebase.

We should instead use the Renderer2 service for DOM manipulation:

constructor(private renderer: Renderer2) {}

ngOnInit() {

this.renderer.addClass(this.elementRef.nativeElement, 'my-class');

}

Although the api is rather different, all of the DOM manipulations which we would usually do using the native DOM api can be done using Renderer2 - some good examples of this can be found here.

3) Be aware of memory management techniques - memory leaks are a showstopper on a Node server.

Whether you are building an Angular application as a single page application or a Universal app, you should always take steps to avoid memory leaks.

However, when your application runs as an SPA, unless there is a huge memory leak, or the user is running the app for an extremely long time without refreshing the page, it is likely that the memory leak will go unnoticed by users.

The same is not true of an Angular app runnning on a Node server - your Node server code and your Angular application code all run in the same environment and share the same memory. Each time a request is made, the server will bootstrap an instance of your Angular app, render the requested page and then clean itself up. The memory used by the application can then be freed up when garbage collection runs.

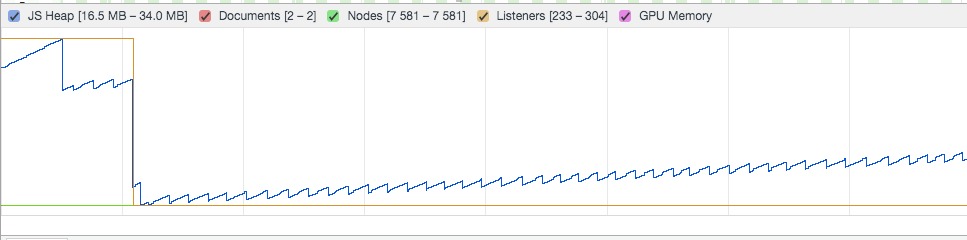

If you have a memory leak of some kind, then each request may leave something behind in memory which cannot be cleaned up, meaning that the memory profile of your app will slowly increase over time, something like the below.

This will eventually result in your Node server running out of memory.

The main thing to do to avoid this issue is to follow best practices for memory management in JavaScript, as well as Angular memory management best practices such as unsubscribing from Observables where necessary.

If you find yourself needing to profile memory usage in Node.js you can use the Chrome debug tools to do this, or use a memory monitoring tool such as node-memwatch.

4) Avoid slow http requests and long running asynchronous operations during the initial page load where possible.

When rendering on the server, Angular will keep track of certain asynchronous operations such as http requests made using HttpClient, and wait for them to complete before rendering the page and serving up index.html.

What are the consequences of this?

In a browser rendered app, if a http request which loads data for some ui element is slow but the rest of the data for the page is available, then the page can still (mostly) be rendered.

When a page renders on the server in a Universal app, a http request which takes a long period of time will block the server render until it receives a response, and increase the load time of the page (ie. the time before the user can begin seeing and interacting with some elements of the page).

You should take the above into consideration when designing your application - if a http request is slow and is blocking the server render of a page, could that request be deferred from the first render and made after the user clicks a button or interacts with the page in some way? Could the page be cached by the server if it’s content doesn’t update often?

Conclusion

We have been through what I have found over the last year or so of working with Angular Universal to be the biggest gotchas. By making a few adaptions to the way you build your application, it will be robust enough to run smoothly in both browser and server environments.

Some resources that helped me to write this article, and that you may also find helpful, are given below.

Helpful Resources

I highly recommend the following Udemy course which has an excellent section on Angular Universal, as well as covering many other Angular concepts (affiliate link):

In addition, the following were really helpful for writing this article, and I very much recommend them as further reading: